Treaty of Box Elder

The following July after the Massacre the Treaty of Box Elder was signed to agree that “friendly and amicable relations be re-established” and that “a firm and perpetual peace shall be henceforth maintained between the said bands and the United States.” After the signing of the Box Elder agreement, government officials attempted to get all of the Northwestern Shoshone to move to the newly founded Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Idaho. After several years of receiving their government annuities at Corinne, Utah, near the mouth of the Bear River, some Shoshone Indians bands finally gave up their homelands in Utah and settled at Fort Hall, where their descendants live today.

Promontory Point

On May 10th, 1869 the rails were completed. According to Grenville Dodge, who was present at the ceremony, “there was quite a mix of ethnic groups at the May 10th ceremony including American Indians.”

Nancy Marinda Tracy Moyes gives this account of the day “Now I will tell a little of the history of the great event that took place at Promontory where the train from the East met the train from the West. The Governor from California stepped off his train to meet the great men from the East. There were many cheers, whistles were shrieking and there [were] lots and lots of noise. Flags were waving and the bands played. Among the hundreds of people gathered, there were also many Indians from the Indian Reservations all decked out in their gaudy buckskin clothes, ornamented with lovely colored beads and with many colored feathers in their bonnets. It is a sight not to be forgotten.”

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in May 1869 made matters even worse for the Northwestern Shoshone. Large numbers of emigrants could now easily reach Utah and compete with the Shoshone and other Indian groups for land and resources. The new railroad also spawned the birth of Corinne in the heartland of the Shoshone domain a development that from its beginning proved to be problematic to the Indians.

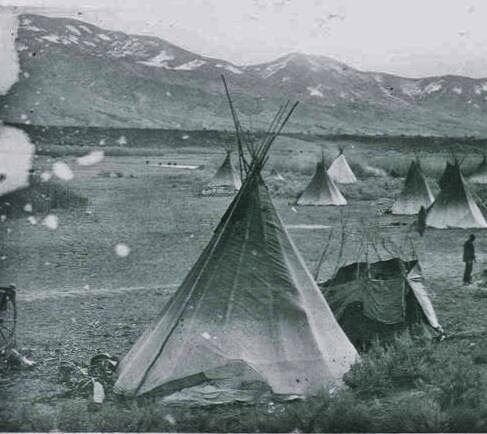

For freight and passengers going from the Central Pacific to the Beaverhead Country by way of the Montana Trail, however, there is a lot of evidence to describe Indian-White relations at the new freight-transfer point at Corinne, Utah. For the Northwestern Shoshone, Corinne was important because the town was located on the west bank of the Bear River just a short distance above it’s confluence with Great Salt Lake and within two or three miles of a traditional winter camp of the Shoshone. Furthermore, this place came to be the site where the Utah Indian Agents distributed the northwestern annuity goods every fall, with Pocatello and his tribe nearly always in attendance. This annual event and the daily comings and goings of various Shoshone groups who camped near the town received constant attention from local newspaper editors.

In 1872 Agent M.P. Berry at Fort Hall complained about the Northwestern Bands of Shoshone. Berry had become increasingly frustrated with the Northwestern bands who drew provisions at Fort Hall but did not remain there. Rather, they “scattered along the Rail Road and among the Mormon settlements.” Berry recommended that they all be sent to Fort Hall permanently.

Conversion to Mormonism

The Northwestern Shoshone appealed to Mormon leader Brigham Young after years of struggle to recover from the massacre. Brigham Young sent George Washington Hill, in the capacity of missionary, to aid them. George W. Hill seemed to be a natural contact for the Northwestern Shoshone seeking to affiliate with Mormonism. He was well known to the Shoshone, having worked with them extensively as a missionary in the Salmon River mission at Fort Lemhi between 1855 and 1859 and occasionally thereafter as a translator. At Hill’s assignment at Salmon River, Hill mastered the Shoshone language and gained a great understanding and respect for the Shoshone people and their culture. The Shoshone honored Hill by acknowledging one of his physical traits in a special name they gave him Inkapompy, meaning “Man with Red Hair.”

At Brigham City, Mormon Bishop Alvin Nichols was also doing his duty by the Indians, distributing beef and other supplies “on a liberal scale” to the encampment of Shoshone. This was in November 1874. The Mormon Church started baptizing Shoshone in the spring of 1875 and set them up farming just a few miles north of Corinne. By August 1875, over 600 Northwestern Shoshones were baptized.

Corinne Settlement

In 1875, the first permanent home for the Northwestern Shoshone was a site near Corinne, Utah. Forced to give up their nomadic lifestyle, the Northwestern Shoshone started learning how to farm, under the guidance of George Washington Hill. There were more than two hundred Indians in camp, with more coming each day. This aroused much apprehension on the part of the people of Corinne who thought the two [Mormons and Shoshone] would unite, in any difficulty which might take place with the Gentiles [non-Mormon people of Corinne].

The people of Corinne made a complaint to the U.S. Army and in late summer 1875, the Shoshone near Corinne were ordered by the U.S. Army to move on to reservations. Many white citizens of Corinne, however, were fearful of a Mormon-Indian alliance, and after wild rumors were started, they called for army protection. The threat of another attack by the army forced the Shoshones to leave the area, abandoning their planted farms and ready to harvest crops.

After their expulsion from their farms by the military, some of the Shoshone moved a few miles north to Elwood, Utah. Others continued to travel farther north to the Fort Hall reservation. Some returned to the Cache Valley to wander in areas they had previously called home.

Washakie

Beginning in the spring of 1876 and continuing into the 1880s, some Northwestern Shoshones applied for land in Box Elder County, Utah, under the Homestead Act, hoping that by doing so they would avoid another Corinne experience. About this time, Isacc Zundel was called by the LDS church to labor with the Shoshone. The objective was to teach the Shoshone farming and industrial practices, encouraging them to become self-sufficient. Other white families were called by the LDS church to settle among the Shoshone on what had now become known as the Malad Indian Farm. Again crops were planted. In addition, lumber was being obtained with which to build houses. Even though the farming experience in this area generally had been very positive, there were still some drawbacks. The size of the land holding was considered to be too small for the number of Indians that were expected to inhabit the farm. Consideration was being given once again settle the Shoshone band in Cache Valley. This idea was discarded in favor of moving the Shoshone band and the farming operation to an area called the Brigham Farm in the Malad Valley. This location was still in Utah, about twenty miles south of Malad, Idaho, and about four miles south or Portage, Utah. The land was purchased from the Brigham City M and M Company, which at that time was managed by Mormon leader Lorenzo Snow. There was a house and a granary already built at a location on the farm, which was about two miles south of what was to become the permanent location of the Washakie settlement, the settlement was named after the respected Shoshone leader Washakie.

Washakie Day School

The Washakie Day School was established in 1882, just two years after settling the village of Washakie. The first teacher was James J. Chandler. Chandler taught the students nursery rhymes and simple songs, presumably to acquaint them with the English language. The students ranged in age from quite young to young adults.

In the 1920’s a new Washakie school building was built. It was an improvement over the old white church building which until this time had served as school classes. For the first time swings, slides, and other playground equipment were brought in and the younger children welcomed a sandbox. First through eight grades were now being taught in the school.

For years the Washakie Community flourished, but population began to decline with the onset of World War II and the availability of better-paying jobs elsewhere. By the early 1940’s many Shoshone had moved away from Washakie and the number of residents dwindled to the point that a school was no longer feasible. The few students remaining were bused to Fielding, Utah for school.

World War II

Like many Indian nations, many members of the Northwestern Shoshone, Washakie Community left during World War II. In 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said, “This generation has a rendezvous with destiny.” When Roosevelt said that he had no idea of how much World War II would make his prophecy ring true. Over seventy years later, Americans are remembering the sacrifices of that generation, which took up arms in defense of the Nation. Part of that generation was a neglected minority, Native American Indians, who flocked to the colors in defense of their country. No group that participated in World War II made a greater per capita contribution, and no group was changed more by that war. During World War II more than 44,000 Native Americans saw military service. They served on all fronts in the conflict and were honored by receiving numerous Purple Hearts, Air Medals, Distinguished Flying Crosses, Bronze Stars, Silver Stars, Distinguished Service Crosses, and three Congressional Medals of Honor.

In spite of years of inefficient and often corrupt bureaucratic management of Indian affairs, Native Americans and stood ready to fight the “white man’s war.” American Indians overcame past disappointment, resentment, and suspicion to respond to their nation’s need in World War II. Native Americans responded to America’s call for soldiers because they understood the need to defend one’s own land, and they understood fundamental concepts of fighting for life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness. Native Americans also excelled at basic training. Maj. Lee Gilstrop of Oklahoma, who trained 2,000 Native Americans at his post, said, “The Indian are the best damn soldiers in the Army.” Their talents included bayonet fighting, marksmanship, scouting, and patrolling. Native Americans took to commando training; after all, their ancestors invented it.

So the government of the United States found no more loyal citizens than their own “first Americans.” When President Roosevelt mobilized the country and declared war on the Axis Powers, it seemed as if he spoke to each citizen individually. Therefore, according to the Indians’ way of perceiving, all must be allowed to participate. About 40,000 Indian men and women aged 18 to 50, left the country and reservations for the first time to find jobs in defense industries. This migration led to new vocational skills and increased cultural sophistication and awareness in dealings with non-Indians. Many members went to work in the defense industries, and others went to war. For some, it was a chance to see the world, for others, a chance to improve their lives with a steady income.

Women took over traditional men’ s duties on the reservation, manning fire lookout stations, and becoming mechanics, lumberjacks, farmers, and delivery personnel. Indian women, although reluctant to leave the reservation, worked as welders in aircraft plants. Many Indian women gave their time as volunteers for American Women’s’ Volunteer Service, Red Cross, and Civil Defense. They also tended livestock, canned food, and sewed uniforms. By 1943, the YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association) estimated that 12,000 young Indian women had left the reservation to work in defense industries. By 1945, an estimated 150,000 Native Americans had directly participated in industrial, agricultural, and military aspects of the American war effort.

For Native Americans, World War II signaled a major break from the past. Many Northwestern Shoshones in the military made a decent living for the first time in their lives. By 1944, the average Native American’s annual income was $2,500, up two and one-half times since 1940. Military life provided a steady job, money, status, and a taste of the modernizing world.

The war, therefore, provided new opportunities for the Northwestern Shoshone, and these opportunities disrupted old patterns. The wartime economy and military service took thousands of Native Americans away from the reservations. Many of these Native Americans settled into the mainstream society, adapting permanently to the cities and to a non-Indian way of life. Moreover, thousands returned to the reservation even after they had proved themselves capable of making the adjustment to white America.

World War II became a turning point for both Native Americans and Caucasians because its impact on each was so great and different. Whites believed that World War II had completed the process of Indian integration into mainstream American society. Large numbers of Indians, on the other hand, saw for the first time the non-Indian world at close range. It both attracted and repelled them. The positive aspects included a higher standard of living, with education, health care, and job opportunities. The negatives were the lessening of tribal influence and the threat of forfeiting the security of the reservation. Indians did not want equality with whites at the price of losing group identification. In sum, the war caused the greatest change in Indian life since the beginning of the reservation era and taught Native Americans they could aspire to walk successfully in two worlds.

A good deal of credit must go to the Native Americans for their outstanding part in America’s victory in World War II. They sacrificed more than most, both individually and as a group. They left the land they knew to travel to strange places, where people did not always understand their ways. They had to forego the dances and rituals that were an important part of their life. They had to learn to work under non-Indian supervisors in situations that were wholly new to them. But in the process, Native Americans became Indian-Americans, not just American Indians.

Washakie Farm Sold

Tanned animal skins were the primary clothing material. Men and women worked to produce clothing all year round. The skins from elk, deer, and antelope made the best dresses or suits. Dresses and suits were decorated with shells and animal claws and teeth. Bones and porcupine quills were also used as adornment. Sinew from animals’ intestine was used as thread. Moccasins were made from deer, elk, and moose hides. Rawhide was the preferred material for the soles, because it was much longer wearing and better able to protect the feet when walking through rocks and rough places. Sometimes moccasins were lined with juniper bark for insulation. When clothing made from skins got wet it had to be removed and vigorously rubbed and stretched until it dried to a soft condition. It was best to actively wear wet moccasins until they became dry to maintain their softness.

Tribe Reorganized

On January 9, 1988, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation Reorganized under the Indian Reorganization Act of June 18, 1934 (48 Stat. 984) as amended; and elected the first Tribal Council under the new constitution.

In January 1995, tribal enrollment of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation numbered 454 members. Nearly all of them live in southern Idaho and northern Utah, with few members scattered throughout the United States.

Massacre Site Saved

On March 24, 2003, with the help of the Trust for Public Land (TPL) Tribal Lands Program, and the American West Heritage Center (AWHC), twenty-six acres of the Bear River Massacre site were donated back to the Northwestern Band of Shoshone Nation.

AWHC initiated the project after completing, with tribal leadership, the planning and design of a cultural and interpretive center at AWHC to help the tribe tell its story. The 26-acre site is in the Bear River Valley, near Preston, Idaho which itself is just north of the Utah-Idaho border. The site is comprised of two parcels, one of 19 acres and the other 7 acres, which TPL purchased privately.

“The massacre site is a sacred and holy spot because the bodies of the Shoshone were never buried, but were left to the wolves and the coyotes to devour. Therefore, it is good that it is finally being recognized and preserved. It is wonderful that the Trust for Public Land is helping save this land.”

Brigham Madsen – Historian

The Trust for Public Land, established in 1972, specializes in conservation real estate, applying its expertise in negotiations, public finance, and law, to protect land for people to enjoy as parks, greenways, community gardens, urban playgrounds, and wilderness. TPL has taken the lead as a national conservation organization to develop a tribal lands program, which will restore to tribes the ownership of lands that contain significant cultural, historical, and natural resource values. Across the nation, TPL has helped protect more than 1.4 million acres.

“This is sacred land to us. It is the burial ground of our ancestors and it is deeply satisfying to have it protected,”

Bruce Parry

Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Executive Director

“We’ve waited many years for this to happen, our dreams have become a reality today.”

Gwen Davis

Northwestern Band Shoshone Tribal Chairwoman

Massacre Site Purchase

In January of 2018 the tribe Was able to purchase 550 acres of the massacre site land. Land they have not been able to use since the massacre in 1863